An Artful Observation of the Cosmos

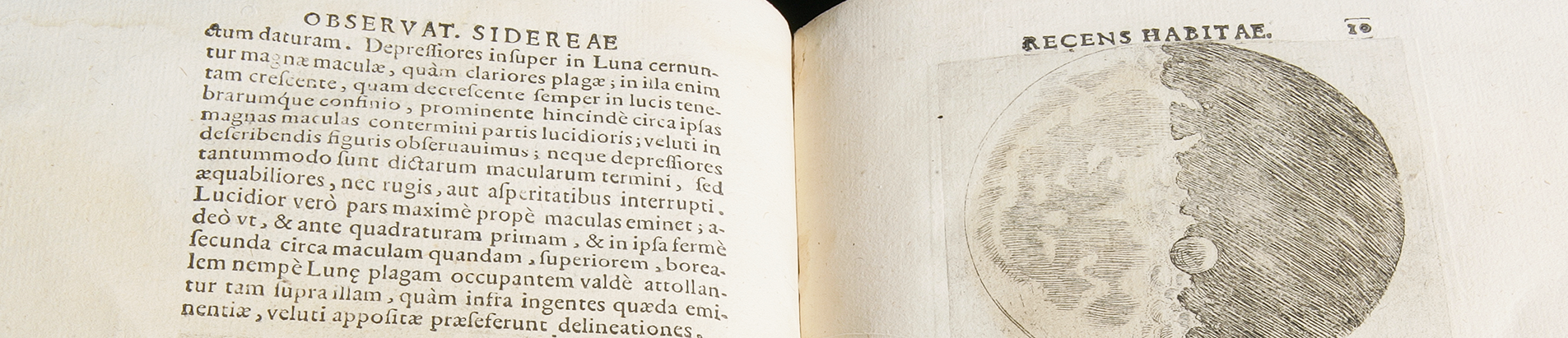

In the Starry Messenger (1610), Galileo reported his discovery of four satellites of Jupiter and mountains on the Moon. These sensational telescopic discoveries would have been impossible were it not for Galileo’s training and experience in Renaissance art. Galileo’s scientific discoveries occurred in the context of an artistic culture which possessed sophisticated mathematical techniques for drawing with linear perspective and understanding of light and shadow.

Exhibit At A Glance

|

Johann Hevelius, Map of the Moon (Selenographia). Gdansk, 1647

|

|

|

|

Francesco Fontana, New Celestial and Terrestrial Observations (Novae coelestium terrestriumq[ue] rerum observationes). Naples, 1646

|

||

|

William Gilbert, New Philosophy, about our World beneath the Moon (De mundo nostro sublunari philosophia nova). Amsterdam, 1651

|

|

|

|

James Nasmyth, The Moon (Der Mond). Leipzig, 1876

|

||

|

Chérubin d’ Orléans, The Optics of the Eye (La Dioptrique Oculair). Paris, 1671

|

|

Explore the Topic

Supplemental resources for a rich educational experience

|

Galileo’s Telescope Learn more about Galileo's telescope. |

|

Drawing Instruments Learn more about the evolution of drawing instruments. |

|

Optical Toys and Anamorphoses Learn more about the historical developemnt of optical toys and anamorphoses. |

|

Galileo's World Exhibit Guide iBook companion to the Galileo's World exhibition |

|

Galileo's World Podcast This series features conversations with experts in diverse fields on Galileo's World. |